Anna Claypoole Peale

Academia and Anatomy in Portrait Miniatures

Academic Article by Kaitlin R. Murdy 2025

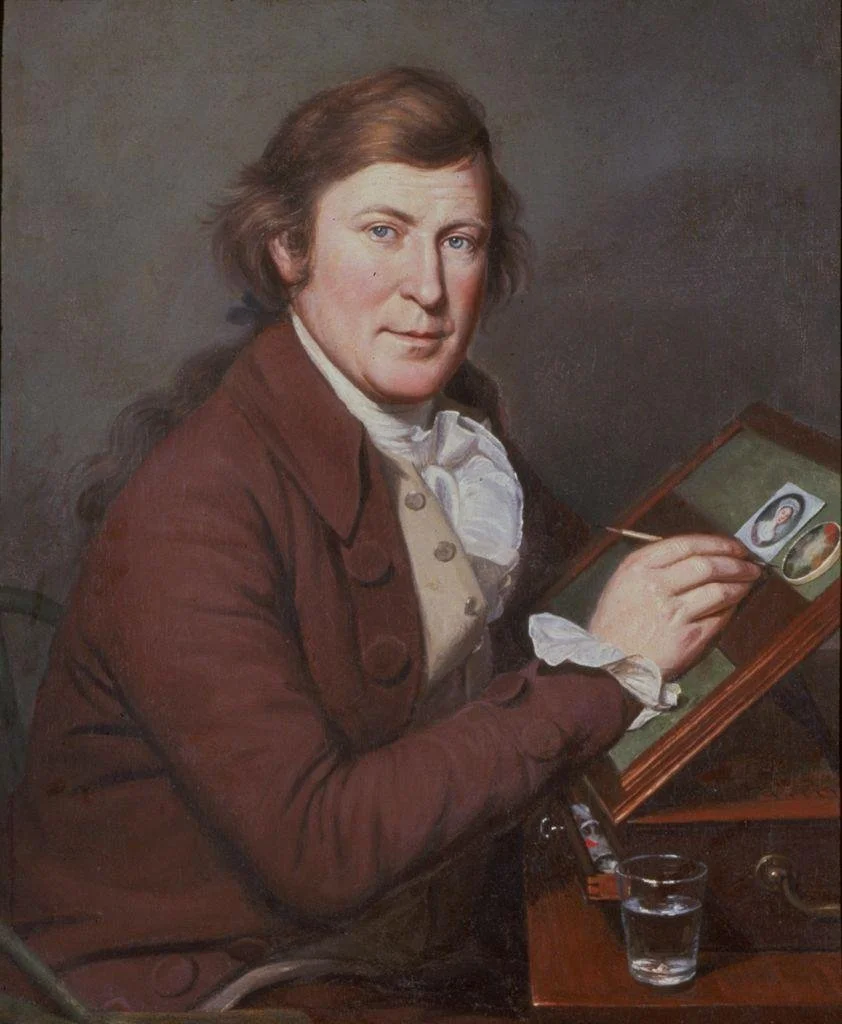

Anna Claypoole Peale was born to James Peale and Mary Claypoole Peale on March 6, 1791. Anna was the fourth child and third daughter of the couple. (Fig. 1) She was the only child to carry on her maternal grandfather James Claypoole’s name into her professional career. A career that lasted over 30 years and produced a documented number of over 160 portrait miniatures. These miniatures included two presidents, senators, an ambassador, scientists, theologians, and numerous individuals from the urban centers of Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, Washington, and Richmond, Virginia. How did Anna become such a successful commissioned-based miniature portraitist? How was Anna’s artistic training treated differently from that of other women artists of the era? What was the extent of training she was allowed to pursue in the realm of anatomy? How did she use this training within her miniature portraits?

Fig. 1 Peale, James (American, 1749-1831). Anna Claypoole Peale. n.d. Oil on canvas, 29 x 24 in.

According to Katie E. McKinney, the word miniature was present even before the inception of the miniature portrait. Derived from the Middle Ages, minium, a red lead oxide used to illuminate manuscripts, later evolved into the Italian term minitura, referring to the small images present in these illuminated manuscripts. It was not until artist Hans Holbein, under the reign of Henry VIII, began to paint miniature court portraits in enamel and on vellum that miniatures began their rise in prominence in Europe. These miniatures were primarily used as gifts in alliances of politics and romance. Queen Elizabeth made similar use of them as rewards for loyalty to individuals. It was also during this time that the wearing of miniatures became a prevalent fashion, particularly among women of the court, often replacing jewels with the tiny portraits. During the 1600s and 1700s, an intense fascination with the act of miniaturization emerged. Many adults collected small novelties such as dolls, dollhouses, kitchenware, and furniture as luxury items for display and entertainment. Among these other miniaturized items came the rise in popularity of miniature portraits, appearing framed in gold, worn on chains, and gracing the tops of snuff boxes. One can see how individuals would wear such portraits with the miniature portrait pair by Thomas Hazlehurst. (Fig. 2) The unanmed woman’s portrait features her wearing a chain with the man’s portrait miniature emphasized in tiny detail.

Fig. 2 Thomas Hazlehurst (British, c. 1740-c. 1821) (artist). Pair of Miniatures: Portrait of a Man and Portrait of a Woman Wearing a Miniature. c. 1780. Watercolor on ivory, Overall: 7 x 5.8 cm (2 3/4 x 2 5/16 in.).

This popularization resulted in the establishment of the Society of Artists in London and the public exhibition of miniature portraits at the Royal Academy in 1760. It is important to note, however, that this rise in popularity did not mean an acceptance of the form with open arms. Sir Joshua Reynolds, president of the Royal Academy, emphasized the noted hierarchy of painting in the Academy. A hierarchy that placed portraits, and thus portrait miniatures, lower on the scale of excellence. He encouraged artists to aim for greatness rather than the minute details. Reynolds also claimed that miniatures were nothing more than acts of tiny imitation and were distracted from a larger philosophical view of humanity and painting: “If deceiving the eye were the only business of the art, there is no doubt, indeed, but the minute painter would be more apt to succeed: but it is not the eye, it is the mind, which the painter of genius desires to address; nor will he waste a moment upon these smaller objects, which only serve to catch the sense, to divide the attention, and to counteract his great design of speaking to the heart.”

Within America, the popularity of the portrait miniature began as early as 1664, with paintings like that of Elizabeth Eggington. (Not pictured) The oil painting by an unknown artist, Elizabeth Cotton Eggington follows conventions of English portraiture. Where sitters wore medals, badges, and miniatures to identify with a particular social identity. The man portrayed in the miniature is surmised to be her father, presenting a familial legacy to her self-identity. Miniature madness reached America soon after the American Revolution and continued into the mid to late eighteenth century. It was around this time that Charles Peale began to establish miniature portraits as art for America. (Fig. 3) He and other artists like John Singleton Copley sought training for miniatures in Europe. In 1764, Charles Willson Peale exhibited 4 miniatures at the Society of Artists in London. Upon the consecration of his museum, Charles presented a multitude of permanent and rotating miniature exhibitions within his museum. These exhibitions ended up displaying the work of Edward Green Melbourne, Richard Cosway, and Thomas Sully.

Fig. 3 Peale, Charles Willson, 1741-1827. James Peale Painting a Miniature. 1795. Oil on canvas, 76 x 63 cm.

We must establish what the artistic academy for women looked like in the era of Anna. The Colonial and Revolutionary periods saw little art production by women outside the home. It was the time of the cult of pure womanhood, and women's place was domesticity. This was particularly present in Quaker-centric Philadelphia. Women were permitted to dabble in the arts, but never be a professional in the field. Quaker women in particular were without much in the field of creativity, with their religion frowning upon public dance, music, drama, and painting. This left them and other women with prose and poetry and handicrafts like embroidery, quilting, shell decoration, and embellishing memorial jewelry. Not only did the religious and social culture of areas such as Philadelphia demand that women make domesticity their primary focus, but also there were few formal schools for instruction in either the fine or applied arts, particularly for women seeking a professional nature in the subject. Apprenticeships with artists were usually only available to boys. Drawing academies for young men and women did exist but did not train their students for a professional field. Schools like; Madame Rivardi’s Seminary for Young Women or Boston Young Ladies Academy of Susanna Rowson, did offer art classes. However, these were intended for amateurs or those seeking cultural refinement. This term, amateur, often described upper-class men and women who, as collectors and patrons of the arts, could theoretically develop more discriminating taste by learning to draw. An amateur’s portfolio of drawings was compiled for pleasure and status rather than for profit.

How did Anna then escape from the amateur label to ascend to that of a professional miniature artist? Well, it certainly had much to do with the family she was born into. One way to professional artistic success for women was to be born or marry into a family of professional artists who could teach and find patrons for their daughters, sisters, or wives. Of course, being born into an artistic dynastic family did not guarantee professional success for such women, with many often never rising beyond the role of copyists. The Peales, however, were one of the most prolific artist families and were exceptionally liberal and enlightened by the standards of the era. (Fig. 4) Charles Wilson Peale and his brother James believed that women had as much right as men to realize their creative potential. Allowing them to produce three generations of women artists, Anna included. From a very young age, Anna would spend hours in her father’s studio watching him craft the miniature portraits. He began to teach her painting skills and eventually the skills required of a miniaturist. Her official apprenticeship for miniatures is said to have lasted for five years, though the exact dates/ages of this are unconfirmed.

Fig. 4 Peale, Charles Willson, 1741-1827. Family Group. 1773. Canvas., 56 1/2 x 89 1/2 inches.

Initially, many miniatures were oil paintings on copper or watercolors on vellum. In the 1720s, ivory became a popular material for miniatures. With this transition, it not only heightened the luxury aspect of the miniature but also the skill to master it. The process was a precise craft that was acquired slowly. The ivory had to be degreased and sanded to prep the surface. From here, the preparatory drawing would be drawn with a light crayon, blunt pin, needle, or ivory piece. These delicate surface incisions created the definition in the image before the application of color. The color was no longer applied using oil paint; instead, a water-soluble pigment, akin to watercolor, made from gum arabic, would be utilized. This pigment not only adhered better to the surface but, when layered correctly, it would produce a desirable gleam. Though erasure was theoretically possible, by blotting out or removing the color with saliva or water, any large mistakes would destroy the work.

One can see why, with such a precise craft, an apprenticeship-type training was primarily used. From a very young age, Anna would spend hours in her father’s studio watching him craft the miniature portraits. He began to teach her painting skills, eventually covering the skills required of a miniaturist. At the age of fourteen, she copied two Vernet paintings, which earned her the hefty sum of thirty dollars at an auction. It was shortly after this that her father began to take her artistic talent more seriously, even being quoted as saying that “painting on ivory was the most suitable employment for a lady,” setting her on the path towards becoming an adept Peale miniature artist. Not only did she have a master instructor in her father, but Anna’s own seeming natural talent and style for miniature work made her very popular for commission work. When examining one of her pieces under magnification (Fig. 5), the surface reveals a meticulously incised design with fine, defining lines for portrait contours and her signature. She would use a needle to create a preparatory study on the ivory, only for her to incise the surface again and overpaint it with contrasting tones to bring clarity to her marks. Details that would be minute in a full-scale portrait, such as hair, lace, and jewelry, were not lost in her images; instead, they were rendered with meticulous detail. Not only were they opaque, but her expert layering and blending of the gum arabic pigment made the surface so shiny it was often mistaken for oil paint.

Fig. 5 Anna Claypoole Peale, American, 1791-1878. Colonel Richard M. Johnson. 1818. Watercolor on ivory, 6.98 x 5.46 cm (2 3/4 x 2 1/8 in.).

Despite her considerable training in miniature, Anna Claypoole Peale presented a full-scale painting at her first exhibition in 1811 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. It wasn’t until 1814, after her father’s retirement, that she exhibited a group of three miniatures at the Pennsylvania Academy's annual spring exhibition. It was shortly after this, between 1817 and 1818, that her career fully developed. One portrait was presented at the 1818 Pennsylvania Academy annual exhibition of Miss Hervey, an English woman renowned for her almost albino complexion. A Philadelphia critique gave the portrait this praise:

“Is by the same young lady, a miniature portrait of the Albiness who was in the city a few weeks past. Nothing can exceed the accuracy and truth of this miniature. Those who have seen the original will confess the resemblance; those who have not, will require no other view to convey to the senses an accurate idea of this sport of nature. The power of light and shade was never more happily managed than in the painting of the hair in this picture.”

After this Anna was overrun with commissions. Due to this onslaught of work and the nature of working at such a minute scale, Anna's eyes suffered from severe inflammation, eventually forcing her to take a break for a brief period during the summer of 1818. Even during and after her recovery, her uncle, Charles wrote to his son Rembrandt; “so many Ladies and Gentlemen desire to sit to her that she frequently is obliged to raise her prices." Her uncle often aided her in her continued success in the field by taking her on painting trips with him and his wife, Hannah, in Washington. Charles used his considerable influence in Washington to help Anna make further connections and notoriety. Between November and February of 1819, Anna and Charles each painted portraits of President Monroe in the White House. (painting locations unknown) Around this time, Major General Andrew Jackson arrived in Washington. He also became a subject for both artists. In Anna’s miniature, she suggested a contrapposto in his pose and used her skills in line work to give his features a level of expressive dynamism. She then chose to position Jackson low in the composition, against a sky filled with clouds. (Fig. 6) Despite attending highbrow events like the President’s New Year’s party, her time in Washington with her aunt and uncle made her restless. She was under the constant scrutiny of her Uncle, who constantly reminded her that the reason she was in Washington was to paint and bolster her career. Anna’s life, both domestic and professional, has been well documented in a number of essays. Yet one point of interest in her academic career is her participation in anatomy courses. This is evident through a letter written while she was staying and working with her Uncle in Washington. On April 7, 1819, Anna wrote to her cousin, Titian Ramsay Peale II:

“My dear Cos. ... I have so much work to do that I hardly know what to do with myself and am looking out the window. ... While sitting at my Painting this afternoon - Mr. [Thomas] Sully came down - to give us tickets and invitations from Mr. Calhoun to attend his anatomical lectures as relating to the arts- Sally [Sarah Miriam] and myself went accompanied by Mr. Sully and three other ladies- we were much interested in a lecture on the human skull - if nothing unforseen prevents we shall attend the whole course which will contain 15 lectures - now don’t you think that we are very scientific ladies”

The nature of her attending these courses is one of a new boldness within her training. At the time the idea of a woman attending anatomical lectures was not socially acceptable. Women and women artists were not permitted to study nude models of either gender and nude art was strict in its viewership. When one looks at her miniature portraits, it may not be thought that the artist had a full grasp of anatomy. Look at her portrait of Major General Andrew Jackson toted as her most successful image. (Fig. 6) She positioned Jackson low on the ivory against a turbulent, cloud-filled sky, with all focus placed upon his face and features. The head is expertly rendered, with a cold compressed smile and dynamism of line. Despite the quality of the head, the body is attempted to portray a slight contrapposto, while only being a bust. Along with this attempt, the shoulders are far too narrow and quite disproportionate to the figure’s head, giving it a kind of bobblehead effect, a trait common in Anna’s work.

Fig. 6 Anna Claypoole Peale, American, 1791 - 1878. Andrew Jackson (1767-1845). 1819. Watercolor on ivory, Overall: 7.9 x 6.2cm (3 1/8 x 2 7/16in.).

With this in mind, what might have been the nature of these anatomy lectures? The instructor was Dr. Samuel Calhoun, who was a staff doctor at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. Considering that his entire series of fifteen lectures focused on the human skull, it suggests that Calhoun may have been considering phrenology. This theory purported to reveal character traits through the physiognomy of the head. Viewing her portraits from this perspective, one can begin to recognize the influence of phrenological training. The best examples of this are her portraits of Mrs. Caroline Sumner Heywood and Samuel Parkman. (Fig. 7) Rather than attempting to capture the anatomical accuracy of her sitters' likenesses, both are instead imbued with phrenological traits. Parkman features a high forehead, a forward, frank gaze, and curled hair that, in combination, are said to represent traits of intelligence and moral integrity. More obvious is that of Mrs. Heywood, who notably features a highly elongated neck. This attribute is commonly used to define youth, beauty, and innocence.

Fig. 7 Anna Claypoole Peale, American, 1791 - 1878. Caroline Sumner Heywood (later Caroline Sumner Heywood Allen, 1796–1887). 1821 Watercolor on ivory,

While Anna Claypoole Peale’s relationship with anatomy in art is not what was expected, the combination of her liberal upbringing and supportive family allowed her to boldly enter a sphere that was generally barred to women. One can see such walls break down for women artists like her with events like the 1807 PAFA exhibition, where many nude and semi-nude antique casts were featured for art instruction. While before women artists may not have been allowed to view such works, a day was set aside known as “Ladies Day” wherein women were allowed to view the nude figures. This was done without the presence and company of men, and although it was not formal education, it was the first instance of unrestricted learning allowed for women.

In the summer of 1820, Rosalba Peale would sit for Anna. The portrait was experimental in its shape and palette, an experimentation Anna felt comfortable doing with a family member rather than a patron. (Fig. 8) The miniature is a three-quarter, half-length in pose with props of a table and drapery, much more similar to traditional full-scale portraits. The more traditional format also included a richer darker palette of black and jewel tones to highlight Rosalba’s light complexion. It was a slightly larger miniature, rather than a handheld keepsake it was to be displayed in a cabinet on a small easel. The format was one explored by neither her uncle nor father and belonged to the younger emerging generation of miniaturists. Despite this, it was obvious that both figures were impressed with the legacy she continued, with Rosalba even being named after Anna’s own miniaturist idol. At the time of the painting, Charles would have been almost eighty years old and two years later would paint the then seventy-three James regarding his daughter’s miniature of her young cousin Rosalba. Within Charles’s portrait of many portraits, a sense of pride can be seen within the expression of James and in the care that Charles renders James and the representation of Rosalba in Anna’s work. While not by original design, a Peale Miniature legacy nonetheless.

Fig. 8 Anna Claypoole Peale, North American; American, 1791-1878. 1820. Miniature: Rosalba Peale. Paintings.

Anna Claypoole Peale: Academia and Anatomy in Portrait Miniatures is an original article by Kaitlin R. Murdy in 2025

Images are used for education and academic analysis.

Bibliography

Hirshorn, Anne Sue. “Portraits in Miniature: Anna Claypoole Peale and Caroline Schetky.” IndexArticles. Index Articles, June 30, 2021. https://indexarticles.com/home-garden/magazine-antiques/portraits-in-miniature-anna-claypoole-peale-and-caroline-schetky/.

Hitshorn, Anne Sue. “Legacy of Ivory: Anna Claypoole Peale’s Portrait Miniatures.” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 64, no. 4 (1989): 16–27. https://doi.org/http://www.jstor.org/stable/41504802.

McKinney, Katie E. “Double Vision: Portrait Miniatures and Embedded Likeness in Early America.” Dissertation, University of Delaware, 2015.

Pethers, Matthew. “Portrait Miniatures: Fictionality, Visual Culture, and the Scene of Recognition in Early National America.” Early American Literature 56, no. 3 (2021): 755+. https://doi.org/Gale Academic OneFile .

Pointon, Marcia. “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England.” The Art Bulletin 83, no. 1 (2001): 48–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177190.

Veloric , Cynthia. “From the Anonymous Lady to the Peales and the Sullys: Philadelphia's Professional Women Artists of the Early Republic.” Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine. Philadelphia Museum of Art, June 18, 2020. https://paheritage.wpengine.com/article/anonymous-lady-peals-sullys/.

“.Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. . Encyclopedia.com. 25 Apr. 2022 .” Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com, May 7, 2022. https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/peale-sisters.

Figures Bibliography:

In order of appearance

Figure 1 Peale, James (American, 1749-1831). Anna Claypoole Peale. n.d. Oil on canvas, 29 x 24 in. Provenance: Mrs. Augustin Runyon Peale, Philadelphia; Provenance: sold to Linden T. Harris, Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania; Provenance: Mrs. Thomas Charlton Henry (Julia Rush Biddle), "Eastdene," Chestnut Hill, Philadephia (died December 31, 1978). https://jstor.org/stable/community.15747075.

Figure 2 Thomas Hazlehurst (British, c. 1740-c. 1821) (artist). Pair of Miniatures: Portrait of a Man and Portrait of a Woman Wearing a Miniature. c. 1780. Watercolor on ivory, Overall: 7 x 5.8 cm (2 3/4 x 2 5/16 in.). Pair of Miniatures 2012.57. The Cleveland Museum of Art; Cleveland, Ohio, USA; Collection: P - British before 1800; Department: European Painting and Sculpture; The Jane B. Tripp Charitable Lead Annuity Trust. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24627545.

Figure 3 Peale, Charles Willson, 1741-1827. James Peale Painting a Miniature. 1795. Oil on canvas, 76 x 63 cm. https://jstor.org/stable/community.13700816.

Figure 4 Peale, Charles Willson, 1741-1827. Family Group. 1773. Canvas., 56 1/2 x 89 1/2 inches. New-York Historical Society. https://jstor.org/stable/community.14628558.

Figure 5 Anna Claypoole Peale, American, 1791-1878. Colonel Richard M. Johnson. 1818. Watercolor on ivory, 6.98 x 5.46 cm (2 3/4 x 2 1/8 in.). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Artstor. https://jstor.org/stable/community.16010374.

Figure 6 Anna Claypoole Peale, American, 1791 - 1878. Andrew Jackson (1767-1845). 1819. Watercolor on ivory, Overall: 7.9 x 6.2cm (3 1/8 x 2 7/16in.). Yale University Art Gallery, American Paintings and Sculpture; Mabel Brady Garvan Collection. Yale University Art Gallery. Artstor. https://jstor.org/stable/community.14714547.

Figure 7 Anna Claypoole Peale, American, 1791 - 1878. Caroline Sumner Heywood (later Caroline Sumner Heywood Allen, 1796–1887). 1821 Watercolor on ivory, Overall: 2 5/16 × 2 5/16 in. (5.9 × 5.9 cm)Yale University Art Gallery, American Paintings and Sculpture; Gift of Mrs. Anthony N. B. Garvan. Yale University Art Gallery. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/77056#technical-metadata

Figure 8 Anna Claypoole Peale, North American; American, 1791-1878. 1820. Miniature: Rosalba Peale. Paintings. Place: The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan, USA, Founders Society Purchase, Gibbs-Williams Fund, 53.345, http://www.dia.org/. https://library-artstor-org.proxybz.lib.montana.edu/asset/AMICO_DETROIT_1039543320.