Pedagogy Of Daughters

An Examination into the Female Contributions to the Education of Girls In Pre- & Post-Revolutionary France

Academic Article by Kaitlin R. Murdy 2019

During the era of French Enlightenment, philosophes revolutionized new ideas in industry, art, and philosophy. A major change came in the form of the education of children and their role in society. Enlightenment writers such as Locke and Rousseau detailed their theories in the proper way to teach French youths. In many of their writings pedagogical treatment for girls was sparse or entirely non-existent. Others such as Fénelon stressed domestic and practical skills as the primary knowledge needed for girls. Writing and teaching alongside these eighteenth century philosophes were a host of female voices. French women who attempt to illustrate an improved education for girls. This essay will examine these Pre- and Post-Revolutionary female writers and their contributions to the pedagogy of girls.

Artist: Abraham Bosse (French, Tours 1602/04–1676 Paris), and Publisher: Jean I Leblond (French, ca. 1590–1666 Paris). The School Mistress. ca. 1638. Etching, Sheet (trimmed): 10 1/16 × 12 3/4 in. (25.5 × 32.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

To fully grasp the advancements these women brought to female education, we must delve into what it looked like before. Contemporary author Samia Spencer gives a very detailed overview of the kinds of public education available to French girls of varied social classes. The most common form of education was convential. As the name suggests, convential education took place in a convent and was taught by the nuns residing there. Almost every aristocratic daughter would attend a convent school, some being held in higher esteem for its attendees. While having any form of schooling was a step forward in the history of women, the nun’s curriculums were far from ideal in their teachings. In Spencer’s essay on Women and Education she mentions the specific convent school, Saint-Cyr. According to Spencer, “Saint-Cyr excluded more subjects than included.” Subjects such as mythology, fictional novels, sciences, philosophy and most history were considered dangerous to the female mind at Saint-Cyr and her sister schools. Instead studies included more domestic subjects such as needlework, sewing, practical crafts, basic writing, arithmetic and religious and moral reading. Putting an emphasis on these moral subjects was the goal to advance female purity and preparation for the students’ future roles of wives and mothers. While constricting in its curriculum, convential education still provided more areas of study than some of the options for the lower classes. Convential education was often not an available opportunity for girls of the lower class families. They still received education in the form of petite écoles and écoles de charité. These minor and charity schools were often still founded by convents but removed more subjects the lower the class of attendees. The minor schools were still taught basic religious reading, writing, and had more of an emphasis on housework training. The charity schools tended to focus strictly on practical skills and housework with little to no reading. The last option of education for young French girls was rural parish schools. These French mandated schools often lacked the space and trained instructors for the female students. If a suitable, preferably female, instructor was found, the rural girls were stuffed into corners of the boys’ schoolroom in an attempt to separate the gendered teaching programs. The only other form of education for girls from impoverished families was the rare vocational schools. These were primarily established in the second half of the eighteenth century. The vocational schools taught technical education, primarily skills within the textile industry. Spinning and lacemaking were two of the most popular subjects taught at these vocational schools. While the vocational schools didn’t teach reading or writing, they were able to open up more opportunity for employment and trade for girls of the lower class. As the age of Enlightenment began to advance so did the role of girls and women in the realm of education.

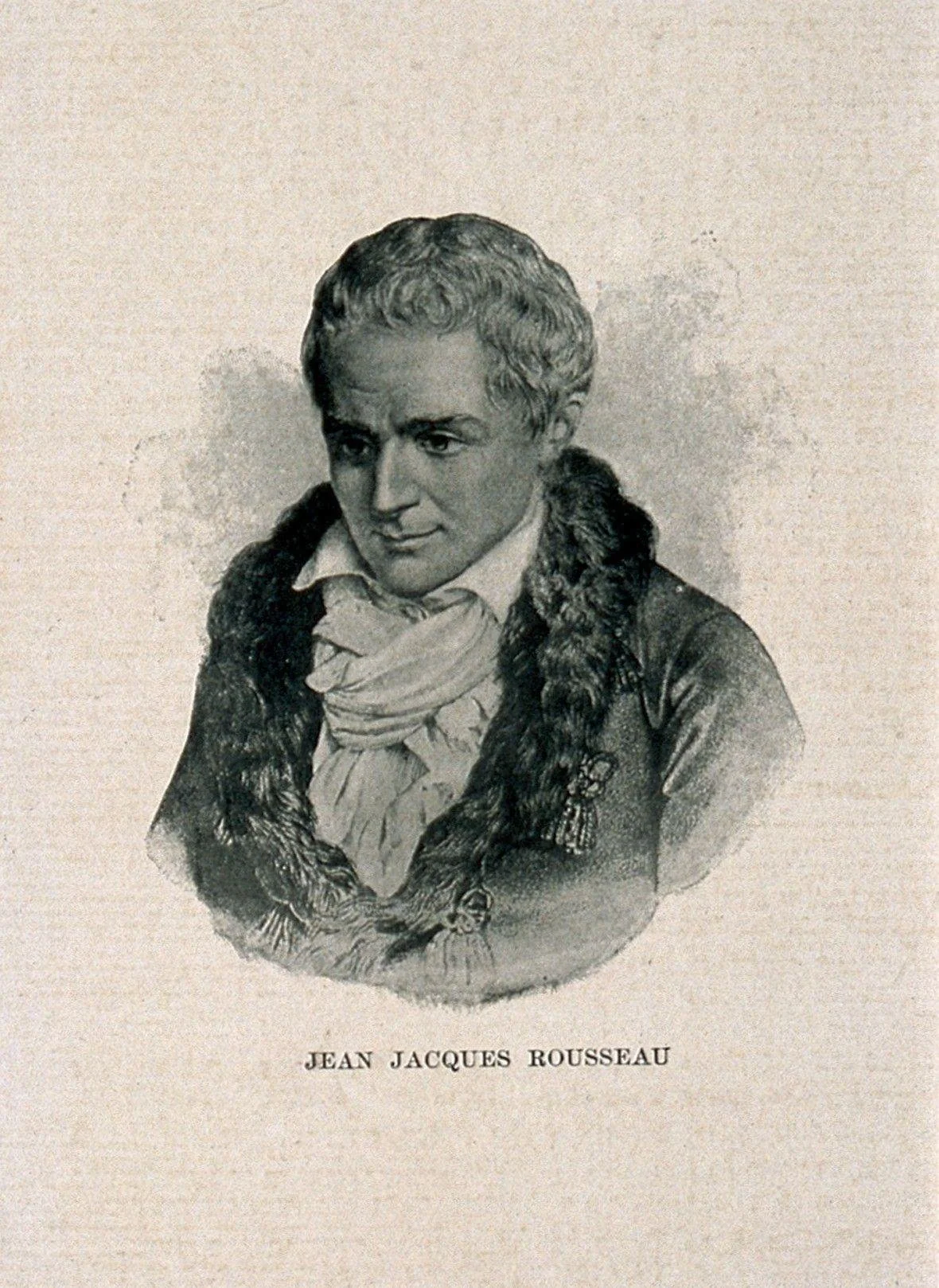

Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Photogravure. n.d. 1 print. Wellcome Collection. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24814656.

Advancements in education and the roles of children in adult society developed with enlightenment thinkers. These thinkers or philosophs, pushed new ideas on how to care and educate children. Rousseau, Locke, and Fénelon were on the forefront of these theories. Many of their teachings were against the severe punishment of children, common at the time. Instead they often proposed patience and understanding of a child’s state of childhood. In Rousseau’s Émile, He instructs the reader to teach the child that passionate, violent anger is akin to a disease. Further, that anger shown in the child should not be met with anger, but treated as sickness, by “[confining] him to his room, and even to his bed...” A disgust for violent punishment was shared among many Enlightenment thinkers. Shared also between writers was that they vied for closer family connections and less time with servants, governesses, or tutors. This meant for the majority of the education of a child coming from the example of the parent. Rousseau, in reference to raising a moral child, “...before you venture undertaking to form a man, you must have made yourself a man; you must find in yourself the example you ought to offer to him...begin by making yourself beloved...”

Marillier, Clément Pierre, 1740-1808., and Giraud, Antoine Cosme, 1760-. Instruments of Education (Woodwork Etc.); and Eight Episodes Related to Rousseau’s Emile in Vignettes on the Wall. Engraving by Giraud Le Jeune after C.P. Marillier, 1788/1793. [1788/1793]. 1 print : engraving, image 13.1 x 8.4 cm.

Enlightenment ideas such as mentioned above are often still used in contemporary teachings on raising and educating children. One may have noticed the language used by Rousseau. He uses masculine gendered articles in reference to his subject. Granted he was writing this of his own young male pupil, the titular Émile. This reference to a male student, however, is common in many of the writings from Enlightenment Philosophes. The mention of French daughters is rarely mentioned if not non-existent in many texts. John Locke rarely mentions female education. This is even considering the fact that he based his own writings on letters written to his cousin Mary Clarke mainly concerning her two eldest children, Edward and Elizabeth (Betty). Mary Clarke begged in a letter to Locke for a set of instructions on the upbringing of young Betty. He reportedly advised for her to be treated to the same form of education as her brother, save for playing in the shade to preserve her fair complexion. In another letter Locke said he felt there was “No gender Distinctions in social development of Moral and Ethical human beings.”

Locke even held a bias towards Betty sending her multiple gifts of books of her request throughout her life. The only mention of instruction of young ladies within his published treatise is similar in its educational equality, “...Beauty in the daughters...the nearer they come to the hardships of their Brothers in their Education, the greater Advantage will they receive from it all the remaining Part of their lives.” The most well-known treatise of education for girls was Fénelon’s L’Education des filles. While solely centered on the pedagogy of girls, its teachings differed little from the current curriculums found in convential education and was certainly not as equal-minded as Locke. Fénelon felt young girls to be inherently immoral and his practices were meant to guard girls against their natural evil tendencies. Fénelon sought to do this through directing girls back towards their role of virtuous wife, mother, and homemaker. His curriculum relied heavily on domestic and practical skills, with sprinklings of the basics of law and arithmetic so that they might run a successful household. Artistic talents were to be tolerated, including, music, needlework, painting, and other artistic ventures. These subjects, along with writing, reading, or learning a second language were to be rewarded only to “...girls with mature judgement and a modest demeanor...” The only other difference in convential and Fenelon’s education was who was meant to be the tutor. Fénelon believed in education of daughters to be implemented by the mother. If the mother was unable to do the task, someone rigorously trained and overseen by her could be appointed.

Fragonard, Honoré, 1732-1799., and Baquoy, Pierre Charles, 1759-1829. François Fénelon as Archbishop of Cambrai Bandaging a Soldier Wounded in the War of Spanish Succession. Engraving by P.C. Baquoy after H. Fragonard. [1820]. 1 print : engraving, with etching, image and border 49 x 40 cm.

Thus far, we have looked at the forms of education available to eighteenth century French girls and the new theories of Enlightenment philosophes. As well as their lack of reference to young girls, whether unchanged from convential education, proposal of equal treatment, or simply removing them from the subject. The last piece to our examination before introducing the three female educators, is the sphere of where education should take place. All three of the women to be introduced come from a different sphere. During this Enlightenment upheaval there was an argument between public or private education. While most philosophes agreed that education should be privately taught in the home by the parents, the education of girls produced more argument than their brothers. Private or public? If privately, should it be a mother or a governess? If publicly, is a Convent still acceptable education or should there be another form of education implemented. Rousseau was wholly against public, monastic teaching for sons and boys, but in one of his few references to daughters says “Convents...are to be preferred to the...home, where a...daughter, always seated under her mother’s eyes, in a closed room, dares not rise, walk, speak, nor breathe, neither does she have a moment of freedom to...indulge in the liveliness common to her age.” Generally, however, it was thought young ladies should be brought up in the home, by their mother, but still be taught practical and domestic skills. There also tended to be a distaste for education of daughters from a governess or other servants. What of religion? Most Enlightenment thinkers were against religion being the basis of all teachings for young boys. For young girls however it was debated whether they should be kept in religious based studies, especially in the early era of Fénelon.

What of our three female educators and writers? Where did they their theories and contributions align within the Enlightenment ideas of education? First it must be mentioned that while only three women writers were chosen for this paper, there was a large amount beyond them writing, teaching, and improving the lives of female students. This paper focuses on Mme d’ Epinay, Mme Campan, and Mme Le Prince de Beaumont. Most of these women were influential both Pre- and Post-Revolution. They all grew up in aristocratic and moyenne bourgeoisie, or middle class, households. Each of these women contributed to the advancement of the role of girls in education of various spheres.

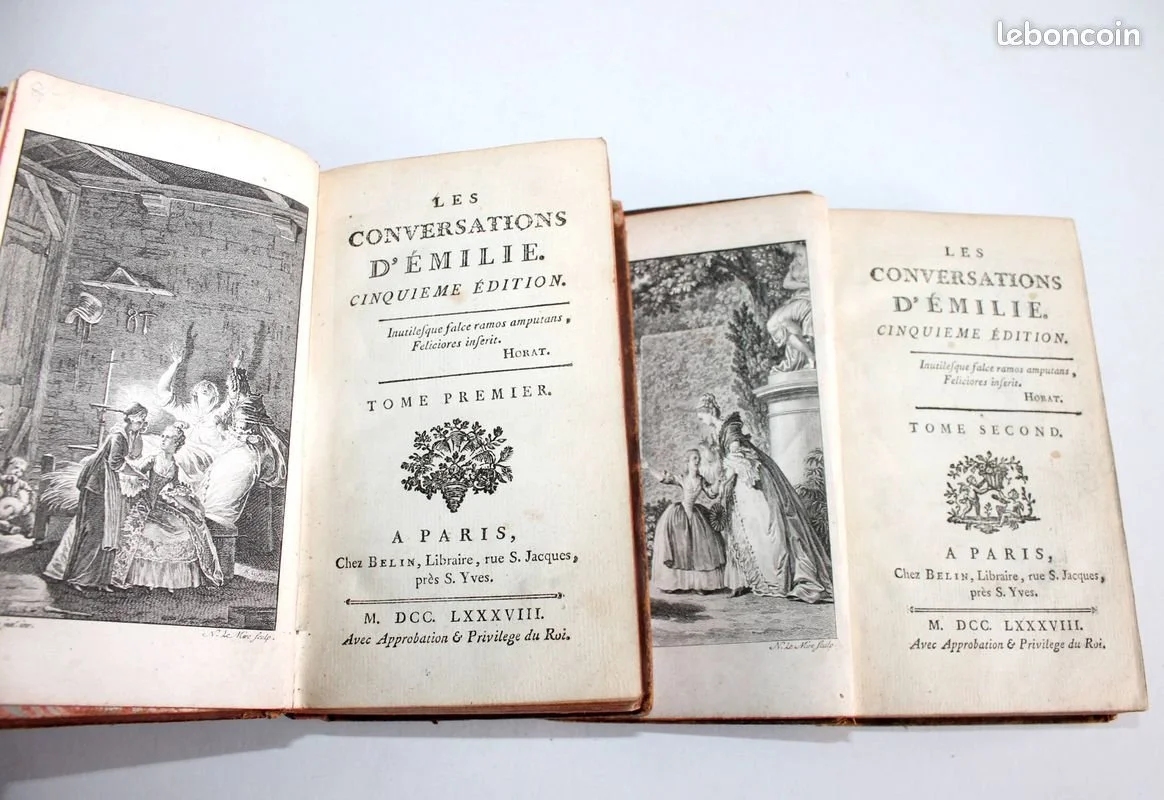

Laur’Art & Collection. LES CONVERSATIONS D’EMILIE. January 3, 2026. Https://Www.Leboncoin.Fr. https://www.leboncoin.fr/ad/livres/2442418321.

Mme d’Epinay falls into the private education. She held similar theories to Enlightenment philosophs, believing education to be best held in the home and instructed by the mother. She was author of Conversations d’Emilie a set of writings detailing her education of her daughter Emilie. It could easily be considered a companion to Rousseau’s Émile, as the relationship portrayed within the writings is similarly tender while instructive. Mme d’Epinay however did begin to introduce more studies to her curriculum. This is compared to the curriculum of the Convents or even the teachings of Fénelon which were considered an ideal in female pedagogy. Instead, Emilie was instructed not only in domestic and artistic ventures but was rigorously trained in subjects of science, history, ethics, writing and penmanship. Her education in reading was similar to contemporary literature courses with a stress on developing critical thinking skills. Religion was still considered highly important and was instructed just as rigorously as all of Emilie’s other subjects. This method of study grew in popularity as a guide for Aristocratic and moyenne bourgeoisie girls education. Mme d’Epinay’s expansion of girls pedagogical subjects removed them from a static role of idle domestic knowledge.

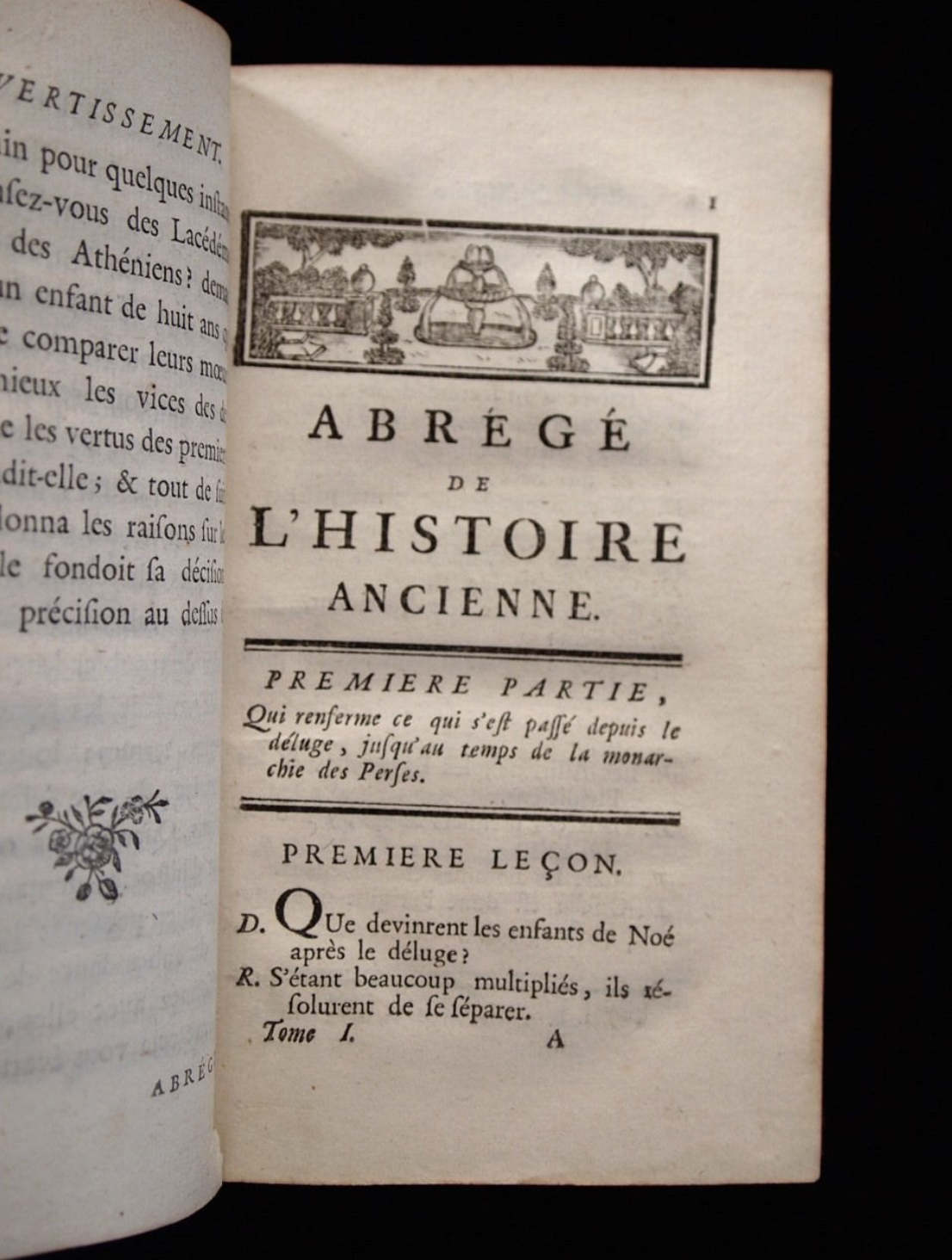

Education complète, ou abrégé de l’histoire universelle, mêlé de géographie et de chronologie. n.d. Librairie Le Feu Follet, Paris, Edition-Originale.

Mme Le Prince de Beaumont also fell into the private sphere of education. Her role was not that of a mother, but the dreaded governess. A governess to an English family between 1745 and 1762. Despite being a governess she was considered an enlightened thinker and wrote nearly seventy children’s books and textbooks. Looking at the novels and texts available to her pupils, Le Prince de Beaumont sought to write for the benefit of the young children she taught. Through her authorship she translated French novels such as the Beauty and the Beast into more digestible stories for young readers. She also penned several of her own fables and novels, portraying children similar to her student’s as the protagonists. Le Prince de Beaumont also created some of the first children’s text books, L’Education complete ou abrégé de l’histoire universelle.

Joseph Boze. Portrait of Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Genet Campan. 1786. Pastel on blue paper, attached to canvas, 81.2 x 64.4 cm. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. Réunion des Musées Nationaux (RMN).

While Mme d’Epinay and Mme Le Prince de Beaumont focused more on the subjects, literature and the domestic sphere of education; Mme Campan sought to improve public education. One of the major complaints of convential schools and other public schools was the lack of trained educators for the girls. Many of the nuns were out of touch with the outside atmosphere of French society and often had little education themselves in the subjects they taught. Mme Campan was a former lady-in-waiting to Marie Antoinette and former reader to the daughters of Louis XV. Having survived the revolution, she founded a public girls school that quickly increased its attendance from three girls to over a hundred within a year. She expanded the subjects taught similar to Mme d’Epinay and used texts intended for the appropriate age group like Mme Le Prince de Beaumont. Her institution, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, was one of the first to institute academic reforms proposed in the eighteenth century, implementing them into Saint-Germain-en-Laye between 1807 and 1814. Many of her students became educators and continued to spread the teachings of Mme Campan, including to the former lower class and rural schools. Mme Campan’s influence in the realm of female pedagogy built on the women and men before her and continued to build through her students.

Writing and educating alongside Enlightenment era Philosophes were several female voices. Voices like Mme d’Epinay, Mme Le Prince de Beaumont, and Mme Campan. Each attempting to improve and advance female education. To expand their studies beyond the religious constriction of the Convents and beyond the equally constricting curriculum of authors like Fénelon. These Pre- and Post-Revolutionary women built upon one another and advanced the pedagogy of French girls into a true era of Enlightenment.

Pedagogy Of Daughters: An Examination into the Female Contributions to the Education of Girls In Pre- & Post-Revolutionary France is an original article by Kaitlin R. Murdy in 2019

Images are used for education and academic analysis.

Bibliography

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, and Barbara Foxley. Emile; Or, Education. London, New York: J.M. Dent & Sons,; E.P. Dutton &, 1911. Print. Everyman's Library. Essays and Belles Lettres ; No. 581.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, Jules Steeg, and Eleanor Worthington. Emile, Or, Concerning Education. Boston: Heath, 1883. Print. Heath's Pedagogical Library ; No. 4.

Spencer, Samia I. French Women and the Age of Enlightenment. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1984. Print.

Locke, John, Jean S. Yolton, and Yolton, John W. Some Thoughts concerning Education. Oxford : New York: Clarendon ; Oxford UP, 1989. Print. Locke, John, 1632-1704. Works. 1975.

Mendelson, Sara. "Child Rearing in Theory and Practice: The Letters of John Locke and Mary Clarke." Women's History Review 19.2 (2010): 231-43. Web.

Fénelon, François De Salignac De La Mothe-. De L'education Des Filles. Goeury, 1828. Web.

Images Bibliography

(In Order of Appearance)

Artist: Abraham Bosse (French, Tours 1602/04–1676 Paris), and Publisher: Jean I Leblond (French, ca. 1590–1666 Paris). The School Mistress. ca. 1638. Etching, Sheet (trimmed): 10 1/16 × 12 3/4 in. (25.5 × 32.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Open: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Artstor. https://jstor.org/stable/community.18335494.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Photogravure. n.d. 1 print. Wellcome Collection. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24814656.

Marillier, Clément Pierre, 1740-1808., and Giraud, Antoine Cosme, 1760-. Instruments of Education (Woodwork Etc.); and Eight Episodes Related to Rousseau’s Emile in Vignettes on the Wall. Engraving by Giraud Le Jeune after C.P. Marillier, 1788/1793. [1788/1793]. 1 print : engraving, image 13.1 x 8.4 cm. Wellcome Collection. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24907523.

Fragonard, Honoré, 1732-1799., and Baquoy, Pierre Charles, 1759-1829. François Fénelon as Archbishop of Cambrai Bandaging a Soldier Wounded in the War of Spanish Succession. Engraving by P.C. Baquoy after H. Fragonard. [1820]. 1 print : engraving, with etching, image and border 49 x 40 cm. Wellcome Collection. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24830407.

Laur’Art & Collection. LES CONVERSATIONS D’EMILIE. January 3, 2026. Https://Www.Leboncoin.Fr. https://www.leboncoin.fr/ad/livres/2442418321.

Education complète, ou abrégé de l’histoire universelle, mêlé de géographie et de chronologie. n.d. Librairie Le Feu Follet, Paris, Edition-Originale. https://edition-originale.com/fr/oeuvres/livres-anciens-1455-1820-2/sciences-6/leprince-de-beaumont-education-complete-ou-abrege-de-l-histoire-universelle-mele-de-geographie-et-de-chronologie-1762-47454?srsltid=AfmBOorz6yHTUMna_5UOENjxGIn7J9py6QYVb0VPJt8kqkzHZPjuiths.

Joseph Boze. Portrait of Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Genet Campan. 1786. Pastel on blue paper, attached to canvas, 81.2 x 64.4 cm. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. Réunion des Musées Nationaux (RMN). Artstor. https://jstor.org/stable/community.15671932.